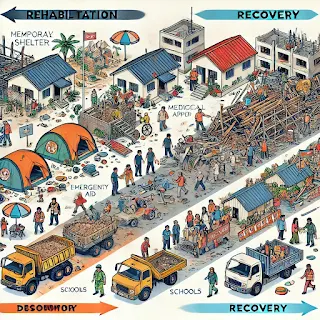

Disaster management involves several phases, including mitigation, preparedness, response, recovery, and rehabilitation. Recovery and rehabilitation are post-disaster activities that aim to restore normalcy and improve resilience in affected areas.

1. Recovery

Recovery is the long-term process of rebuilding communities, infrastructure, economy, and social systems after a disaster. It focuses on restoring normalcy while incorporating resilience measures to withstand future disasters.

- Short-term Recovery – Immediate efforts within weeks or months to restore essential services (e.g., water, electricity, healthcare, shelter).

- Long-term Recovery – Efforts that take months to years, including rebuilding infrastructure, economic revitalization, and mental health support.

- Resilience – The ability of a community to recover quickly and adapt to future disasters.

- Livelihood Restoration – Providing economic support to affected populations through job creation, skill training, and financial assistance.

- Psycho-social Recovery – Addressing trauma, stress, and mental health impacts of disasters.

- Infrastructure Reconstruction – Rebuilding damaged roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools.

- Economic Recovery – Providing financial aid, loans, and policies to restore businesses and agriculture.

Example

- 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami: Long-term recovery efforts included the reconstruction of houses, fishing boats, and economic support for affected communities.

- 2015 Nepal Earthquake: The government and NGOs provided financial support, rebuilt schools, and restored tourism-dependent economies.

2. Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation is the process of restoring the physical, social, and economic conditions of an affected community to at least pre-disaster levels. It focuses on providing temporary solutions before permanent recovery measures are implemented.

- Temporary Housing – Setting up relief shelters or camps for displaced populations.

- Medical Rehabilitation – Providing healthcare, prosthetics, and therapy to disaster survivors.

- Social Reintegration – Reuniting displaced families and providing psychological counseling.

- Environmental Rehabilitation – Restoring ecosystems, clearing debris, and managing waste.

- Cash-for-Work Programs – Engaging affected people in rebuilding efforts by providing financial incentives.

Example

- Hurricane Katrina (2005): Temporary shelters were set up, and medical rehabilitation was provided for injured victims.

- Uttarakhand Floods (2013): Government agencies set up temporary housing and provided psychological counseling to affected families.

Differences

| Aspect | Recovery | Rehabilitation |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Long-term rebuilding and resilience | Short-term restoration of essential services |

| Timeframe | Months to years | Days to months |

| Focus | Infrastructure, economy, mental health, sustainability | Immediate shelter, healthcare, livelihood support |

| Outcome | Sustainable development and disaster preparedness | Basic functioning and stability |

Comments

Post a Comment